Background

Before regional distinctions formed, barbecue abided by a simpler set of instructions—it was merely smoked meat (any type that was available) cooked outside, intended for large groups of people.“Barbecue as we know it today is a combination of Western European meets Native American techniques,” says Robert Moss, the author of Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, the first full-length history on the subject.

Barbecue as we know it today is a combination of Western European meets Native American techniques.— Robert Moss, the author of Barbecue: The History of an American Institution

Despite its deep association with the South, the practice initially took hold along the Atlantic Coast in North America. “Around the turn of the 18th century, Spanish and British colonists were cooking meat barbecue-style along the coast,” Moss says. “Some of the earliest mentions of barbecue came from New England.” From there, it spread to Virginia, where it evolved to become one of the primary forms of social entertainment. It continued southwards, down to the Appalachians and Carolinas; to Georgia and Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky; and eventually, by the 1840s, to Mississippi and Texas.

“Barbecue just got bigger and bigger in the 19th century and was more formalized as a social ritual,” Moss says. “It was standard during elections and became a way for the community to celebrate the Fourth of July in the South. Hundreds to thousands of people would come to roast cows, pigs, and sheep.

Election candidates and public officials were quick to utilize the barbecue to their advantage. “It was the best way to get a bunch of people together to hear your message,” Moss notes. “Barbecues would become partisan debate affairs and also a form of civic celebration.

A 19th-century roast relied on whatever was available. “There was no refrigeration at all, and it was whatever livestock they had on stand that they could spare.” (Think sheep, lambs, goats, venison, and turkey.) “It would be butchered on-site, dressed, and then put on the pits. The animals would be laid on wood poles or iron bars. There was a basting sauce that was some combination of butter, vinegar, salt, and red pepper.”

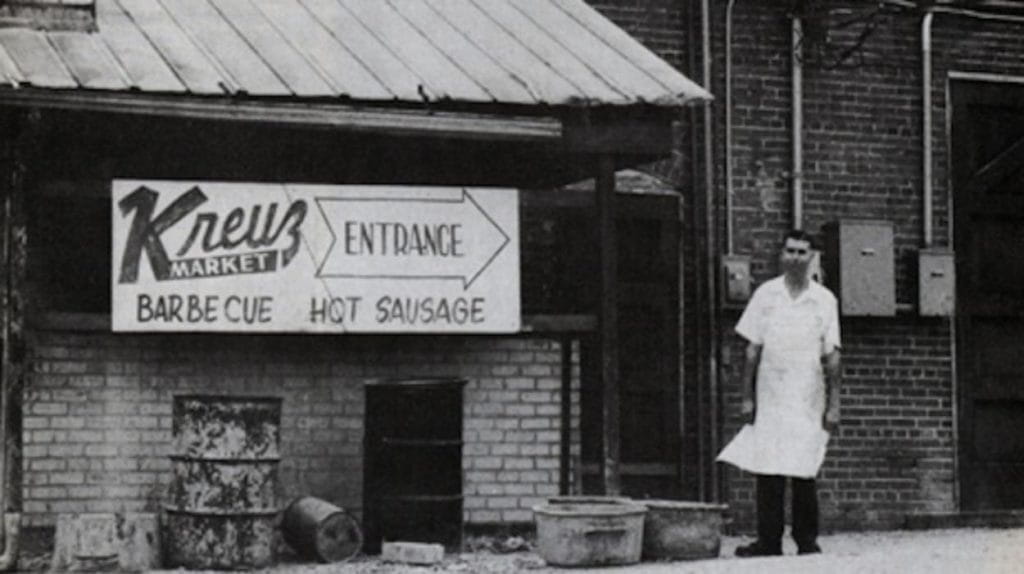

“Toward the end of the 19th century, some of the barbecue men became famous. They would start cooking barbecue and bringing it into town for the weekend.” Thus began the tradition of roadside barbecue stands, which eventually paved the way for restaurants.

There was no refrigeration at all, and it was whatever livestock they had on stand that they could spare.

“It evolved over time,” Moss says. “The earliest restaurants were cooking meat in a trench dug into the ground. Around the 1920s and 1930s, restaurants started building permanent brick pits.” This evolution helped fuel the rivalries between regional styles.

“Each region got its own style of restaurant because if you’re cooking on a weekly or daily basis, you have to settle on a specific cut,” Moss says. Barbecue joints ended up focusing on the one or two meats that were most common in their area, as well as sides like watermelon and bread that wouldn’t spoil.

Slowly, various restaurants started to develop their own signature flourishes, including distinct sauces. North Carolina touted slaw and hush puppies. Texans vouched for brisket with onions and pickles.

“The barbecue restaurant dominated the American restaurant market form the ’30s to the ’50s. It spread all along the Florida roadsides to California. By the late 19th century to the 20th century, it had gone everywhere except for the Northeast,” Moss said.

But a new dining trend would soon come along to crush barbecue’s reign. That nemesis? Fast food.

“In the ’50s, Burger King and McDonald’s came on the scene. McDonald’s actually began as a barbecue joint; that was their specialty. But because it was a tight margin and a really competitive scene, they shut down their restaurant for a couple of months and replaced it with burgers, fries, and shakes. They cut their prices and made up for it in volume,” Moss says.

McDonald’s actually began as a barbecue joint; that was their specialty. But because it was a tight margin and a really competitive scene, they shut down their restaurant for a couple of months and replaced it with burgers, fries, and shakes.

By the ’60s and ’70s, it was getting harder for pitmasters to make a living. The main issue was that, unlike the increasingly popular fast-food joints, barbecue took an extremely long time to make. The food simply could not compete.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that people started to rediscover barbecue. A variety of factors played a role in this revival, including the competition barbecue circuit and the Food Network. These days, a lot of classically trained chefs are interested in cooking with wood again.